Sunwin 🎖️ Link Tải Sunwin Chính Chủ Mới Nhất Không Chặn

Sunwin là một trong những cổng game bài đổi thưởng trực tuyến lớn nhất hiện nay. Với sự phát triển mạnh mẽ và được cấp phép bởi Ủy ban cờ bạc quốc tế, Sun win không chỉ thu hút người chơi bởi đa dạng loại hình game mà còn nhờ vào hệ thống bảo mật cao, giao dịch nạp/rút tiền dễ dàng và dịch vụ chăm sóc khách hàng tận tình.

Tìm hiểu về nhà cái Sunwin

Khi nhắc đến nhà cái Sunwin, nhiều người chơi thường có những cảm nhận tích cực về trải nghiệm cá cược của mình. Bởi lẽ, https://automobileinsurance.us.com/ không chỉ đơn thuần là một nền tảng cho việc chơi game mà còn là một cộng đồng nơi mà mọi người có thể thư giãn và tìm kiếm cơ hội thắng lợi.

Lịch sử hình thành và phát triển của Sunwin

Sunwin được thành lập với mong muốn cung cấp một sân chơi an toàn và chất lượng cho những người yêu thích game bài và cá cược trực tuyến. Được điều hành bởi Suncity Group, một trong những tập đoàn hàng đầu trong lĩnh vực giải trí, Sunwin nhanh chóng khẳng định vị thế của mình trên thị trường.

Trải qua nhiều năm hoạt động, nhà cái Sunwin đã không ngừng mở rộng danh mục sản phẩm và dịch vụ của mình để đáp ứng nhu cầu ngày càng đa dạng của người chơi. Từ game bài cổ điển như tiến lên miền Nam và xì dách đến các trò chơi live casino hấp dẫn như poker và baccarat, Sunwin thực sự mang đến một trải nghiệm phong phú và thú vị.

Những điểm nổi bật của nhà cái Sunwin

Một trong những yếu tố làm nên sự khác biệt của Sunwin chính là mức độ chuyên nghiệp trong từng khâu phục vụ người chơi. Hệ thống bảo mật của nhà cái được đánh giá rất cao với mã hóa SSL 124-bit, đảm bảo thông tin cá nhân cũng như tài khoản của người chơi luôn được bảo vệ an toàn.

Ngoài ra, Sunwin cung cấp nhiều phương thức nạp rút tiền đa dạng như ngân hàng, ATM, thẻ cào và ví điện tử, giúp người chơi dễ dàng thực hiện giao dịch mà không gặp khó khăn nào. Dịch vụ chăm sóc khách hàng của Sunwin cũng rất tốt, hỗ trợ người chơi qua nhiều kênh khác nhau như hotline, Telegram, chatbox, Messenger và email.

Tại sao nên chọn nhà cái Sunwin?

Với những lý do trên, không khó hiểu khi nhiều người chơi lựa chọn nhà cái Sunwin làm điểm đến cho những trải nghiệm cá cược của họ. Chưa kể, việc đăng ký tài khoản hoàn toàn miễn phí và nhanh chóng còn là một điểm cộng lớn cho những ai mới bắt đầu tham gia vào thế giới game online.

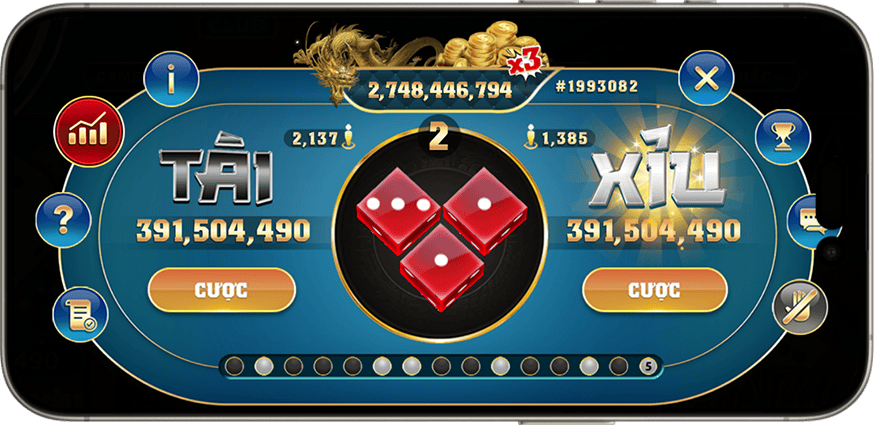

Các loại game hấp dẫn tại nhà cái Sunwin

Một trong những điểm thu hút lớn nhất của nhà cái Sunwin chính là danh mục game đa dạng và phong phú. Việc bạn có thể lựa chọn từ nhiều loại hình game khác nhau không chỉ giúp giảm bớt sự nhàm chán mà còn tạo ra cơ hội để bạn nâng cao kỹ năng chơi game của mình.

Game bài truyền thống

Nhà cái Sunwin cung cấp nhiều trò chơi bài truyền thống, nổi bật là tiến lên miền Nam và xì dách. Những loại game này không chỉ quen thuộc với người Việt mà còn mang tính giải trí cao, giúp bạn có những phút giây thư giãn thoải mái.

Chơi tiến lên miền Nam tại Sunwin, bạn sẽ cảm nhận được sự hồi hộp khi phải đưa ra những quyết định nhanh chóng, đối đầu với những đối thủ trong bàn. Chiến thuật và may mắn là hai yếu tố quan trọng giúp bạn có được chiến thắng.

Xì dách, một trò chơi cũng rất phổ biến, không chỉ dựa vào khả năng tính toán mà còn phụ thuộc vào khả năng đọc tâm lý đối phương. Sunwin mang đến cho bạn trải nghiệm sống động nhất khi thi đấu với những người chơi khác trên toàn thế giới.

Live Casino

Bên cạnh đó, phần live casino của nhà cái Sunwin thực sự là một trải nghiệm mà bạn không nên bỏ lỡ. Các trò chơi như poker, baccarat và roulette đều được tổ chức dưới hình thức trực tiếp, nơi bạn có thể tương tác với dealer và các người chơi khác.

Sự thật là, việc chơi live casino mang lại cảm giác chân thật hơn rất nhiều so với việc chơi game thông thường. Bạn sẽ cảm thấy như đang ở trong một sòng bạc thực thụ, với âm thanh, hình ảnh rõ nét và sự hấp dẫn từ những vòng quay của bánh xe roulette hay những lá bài được chia ra.

Điều này không chỉ giúp tăng thêm sự thú vị mà còn tạo ra cơ hội cho bạn gặp gỡ và kết nối với những người chơi khác từ khắp nơi, cùng chia sẻ đam mê và kinh nghiệm chơi game.

Slots và Mini Games

Nếu bạn yêu thích sự nhanh chóng và tiện lợi, các trò chơi slots và mini games tại nhà cái Sunwin sẽ là lựa chọn lý tưởng. Những trò chơi này thường có cách chơi đơn giản và dễ hiểu, phù hợp với cả những người mới bắt đầu.

Slots tại Sunwin thường được thiết kế với đồ họa đẹp mắt, âm thanh sống động, giúp người chơi dễ dàng đắm chìm trong trải nghiệm chơi game. Với nhiều chủ đề và mô hình khác nhau, bạn sẽ luôn tìm thấy điều gì đó mới mẻ và hấp dẫn.

Mini games cũng là lựa chọn tuyệt vời cho những ai muốn thử vận may của mình mà không phải tốn quá nhiều thời gian. Những trò chơi này thường có thời gian chơi ngắn, rất thích hợp cho những lúc bạn muốn thư giãn nhanh chóng.

Cách đăng ký và tham gia nhà cái Sunwin

Để bắt đầu trải nghiệm tại nhà cái Sunwin, trước tiên bạn cần thực hiện một số bước đơn giản để đăng ký tài khoản. Quy trình này được thiết kế dễ dàng, giúp người chơi nhanh chóng gia nhập vào cộng đồng của Sunwin.

Hướng dẫn đăng ký tài khoản

Để tạo tài khoản tại nhà cái Sunwin, bạn chỉ cần truy cập vào trang web chính thức của nhà cái. Sau đó, tìm nút “Đăng ký” và điền vào mẫu thông tin yêu cầu, bao gồm tên đăng nhập, mật khẩu, số điện thoại và địa chỉ email.

Sau khi điền đầy đủ thông tin, bạn hãy kiểm tra lại để đảm bảo rằng mọi thông tin đều chính xác, sau đó nhấn nút “Gửi”. Nhà cái sẽ gửi một mã xác nhận đến email hoặc số điện thoại của bạn để hoàn tất quá trình đăng ký.

Đăng nhập vào tài khoản

Khi đã đăng ký tài khoản thành công, bạn có thể dễ dàng đăng nhập vào nhà cái Sunwin bằng cách nhập tên đăng nhập và mật khẩu của mình. Trang chủ sẽ hiển thị các trò chơi và dịch vụ mà bạn có thể tham gia.

Việc đăng nhập rất đơn giản, tuy nhiên bạn cần lưu ý bảo mật thông tin tài khoản của mình. Không nên chia sẻ mật khẩu với bất kỳ ai và thay đổi mật khẩu định kỳ để đảm bảo an toàn.

Nạp tiền và rút tiền

Khi đã có tài khoản, bạn có thể bắt đầu nạp tiền vào tài khoản để tham gia chơi game. Tại nhà cái Sunwin, quá trình nạp tiền rất nhanh chóng và thuận tiện với nhiều phương thức như chuyển khoản ngân hàng, rút tiền qua ATM, sử dụng thẻ cào hoặc ví điện tử.

Tương tự, khi bạn muốn rút tiền thắng cược, chỉ cần truy cập vào phần rút tiền, chọn phương thức rút và nhập số tiền cần rút. Nhà cái Sunwin cam kết xử lý các giao dịch một cách nhanh chóng và an toàn.

Dịch vụ chăm sóc khách hàng tại nhà cái Sunwin

Một yếu tố không thể bỏ qua khi nhắc đến nhà cái Sunwin chính là dịch vụ chăm sóc khách hàng. Đội ngũ nhân viên của nhà cái luôn sẵn sàng hỗ trợ người chơi 24/7, đảm bảo mọi thắc mắc và vấn đề sẽ được giải quyết kịp thời.

Các kênh hỗ trợ khách hàng

Người chơi có thể liên hệ với đội ngũ hỗ trợ của Sunwin qua nhiều kênh khác nhau như hotline, Telegram, chatbox, Messenger, và email. Mỗi kênh đều có ưu điểm riêng, giúp người chơi tiện lợi hơn trong việc liên lạc.

Hotline là lựa chọn hàng đầu cho những vấn đề khẩn cấp, khi bạn cần nhanh chóng nhận được tư vấn. Trong khi đó, các nền tảng nhắn tin như Telegram hay Messenger mang lại sự thuận tiện, cho phép bạn gửi tin nhắn và nhận phản hồi ngay lập tức.

Phản hồi từ người chơi

Nhiều người chơi đã có những phản hồi tích cực về dịch vụ chăm sóc khách hàng của nhà cái Sunwin. Họ cho biết đội ngũ nhân viên rất nhiệt tình, chuyên nghiệp và luôn sẵn sàng lắng nghe, giúp đỡ khi cần thiết.

Điều này không chỉ tạo ra sự yên tâm cho người chơi mà còn chứng tỏ rằng Sunwin rất coi trọng sự hài lòng của khách hàng. Những phản hồi tích cực này chắc chắn sẽ thúc đẩy nhà cái phát triển hơn nữa trong tương lai.

Chính sách bảo mật thông tin

Ngoài việc cung cấp dịch vụ chăm sóc khách hàng tận tình, nhà cái Sunwin cũng chú trọng đến vấn đề bảo mật thông tin. Thông tin cá nhân của người chơi sẽ được bảo mật và không bao giờ bị chia sẻ với bên thứ ba.

Nhà cái sử dụng công nghệ mã hóa SSL 124-bit, một trong những tiêu chuẩn bảo mật cao nhất hiện nay, đảm bảo rằng mọi giao dịch và thông tin cá nhân đều được bảo vệ an toàn tuyệt đối. Điều này giúp người chơi có thể an tâm tham gia vào các trò chơi mà không lo lắng về vấn đề bảo mật.

Trong thế giới game bài đổi thưởng trực tuyến hiện nay, nhà cái Sunwin đã khẳng định được vị thế của mình như một trong những cổng game hàng đầu châu Á. Nhờ vào sự đa dạng trong các loại hình game, dịch vụ chăm sóc khách hàng tận tình và hệ thống bảo mật cao, Sunwin thực sự mang đến những trải nghiệm tuyệt vời cho người chơi.

Dù bạn là người mới bắt đầu hay là một tay chơi có kinh nghiệm, Sunwin luôn có điều gì đó để bạn khám phá và trải nghiệm. Hãy tham gia ngay hôm nay để không bỏ lỡ những cơ hội thú vị và tiềm năng thắng lớn tại nhà cái Sunwin!

Đối tác Sunwin chính thức: https://pinkfloydfan.net/